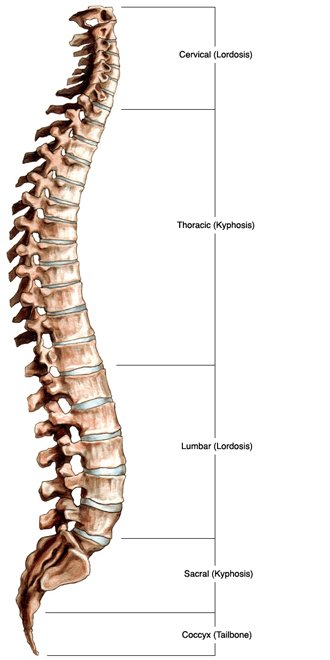

When spinal anatomy is viewed from the front, the spine appears straight and rigid; however, when viewed from the side, a healthy spine is slightly S-shaped, with distinct curves. The curves are necessary for shock absorption and normal healthy movement.

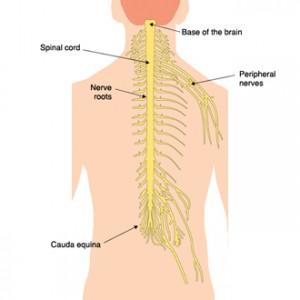

The spinal column:

- Protects the spinal cord and nerve roots

- Provides structural support and balance to maintain an upright posture

- Enables flexible motion

Spinal Anatomy: Regions of the Spine

Cervical Spine

The neck consists of seven vertebrae, abbreviated C1 through C7. These vertebrae protect the brain stem and the spinal cord, support the skull and allow for a wide range of head movement.

Thoracic Spine

The chest area contains the 12 thoracic vertebrae, abbreviated T1 through T12.

Rib attachments add to the strength and stability of the thoracic spine. The thoracic spine is often less prone to injury because it is braced by the rib cage. Additionally, thoracic vertebrae do not rotate as much as vertebrae in the neck or lower back,

Lumbar Spine

The lower back consists of 5 vertebrae, abbreviated L1 through L5. The lumbar vertebrae are the largest in the spine and bear most of the body’s weight. The lower back is particularly vulnerable to injury because it bears the stress of virtually all motion, i.e., sitting/standing, pushing/pulling, and lifting. The lumbar spine has more range of motion than the thoracic spine but less than the cervical.

Sacral Spine

Five vertebrae fused together in the lower spine form the sacrum, abbreviated S1 through S5. The sacrum is a triangular-shaped structure that lies between the “wings” of the pelvis and is held together by the sacroiliac joints. The last lumbar vertebra (L5) articulates (moves) with the sacrum. Just below the sacrum are 3-5 coccygeal vertebrae, which are also fused together. These form the coccyx, more commonly referred to as the tailbone.

Cauda Equina

At the end of the spinal cord, there is a collection of nerve roots known as the cauda equina, or horse’s tail. Even though the spinal cord ends in the upper portion of the lumbar spine (near L-1), this collection of nerve rootlets continues down the spinal canal and becomes the nerves that send and receive all of the information to/from the pelvis and lower extremities. If these nerve roots become damaged, motor and sensory functions in the bladder and legs can be affected. Sometimes, even permanent paralysis can occur.

Although rare, Cauda equina syndrome (CES) usually occurs as a result of trauma or complications related to a lumbar herniated disc. Patients with back pain should be aware of the following symptoms:

- Severe low back pain

- Weakness and/or loss of sensation in the legs or groin

- Urinary retention; urinary or bowel incontinence

Cauda equina syndrome is a medical emergency. Left untreated, the loss of function can become permanent.

Spinal Curves

A kyphotic curve is convex (i.e., curves outward). The curves in the thoracic and sacral spine are kyphotic.

A lordotic curve is concave (i.e., curves inward) and is found in the cervical and lumbar levels of the spine.

Vertebral Structures

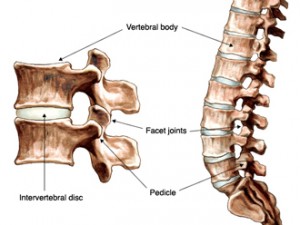

The outer shell of a vertebra consists of cortical bone. Cortical bone is dense, solid, and strong. Inside each vertebra is cancellous bone, which is less dense than cortical bone and consists of loosely knit structures that resemble a honeycomb. Bone marrow, which forms red blood cells and some types of white blood cells, is found within the cavities of cancellous bone. Vertebrae consist of the following common elements:

Body: The body is the largest part of a vertebra. Viewed from overhead, it appears oval. From the side, it appears slightly hourglass-shaped, thicker at the ends and thinner in the middle.

Axial and lateral views of a thoracic vertebral body

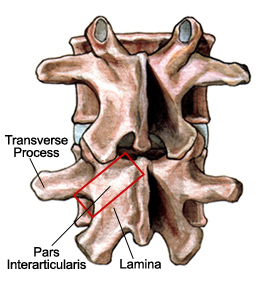

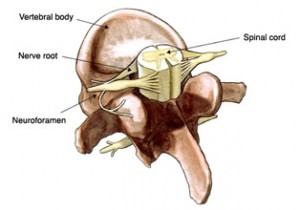

Pedicles: Two short processes made up of strong cortical bone protrude from the back of the vertebral body.

Laminae: Two relatively flat plates of bone that extend from the pedicles on either side and join in the midline.

Processes: There are three types of processes: articular, transverse, and spinous. The processes serve as connection points for ligaments and tendons.

Spinous processes extend posteriorly from vertebrae where the two laminae join and act as a lever to effect vertebral motion.

Facet joints: Four articular processes join with the articular processes of adjacent vertebrae to form the facet joints. The facet joints, along with the intervertebral discs, allow for motion in the spine. These joints are visible at the back (posterior) of each vertebral body. Facet joints help the spine to bend, twist, and extend in different directions. The facet joints restrict excessive movement, such as hyperextension and hyperflexion (e.g., whiplash). Each vertebra has two facet joints. The superior articular facet faces upward and works like a hinge with the inferior articular facet (below). Like other joints in the body, each facet joint is surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue and produces synovial fluid to nourish and lubricate the joint. The surfaces of the joint are coated with cartilage that helps each joint to move (articulate) smoothly.

Endplates: The top (superior) and bottom (inferior) of each vertebral body are coated with an endplate. Endplates are complex cartilaginous structures that blend into the intervertebral disc and help support the disc.

Intervertebral Foramen: The pedicles have a small notch on their upper surface and a deep notch on their bottom surface. These notches form a hollow passageway between vertebrae termed a neural foramen. These neural foramen act as windows for the nerve roots to exit the spinal canal.

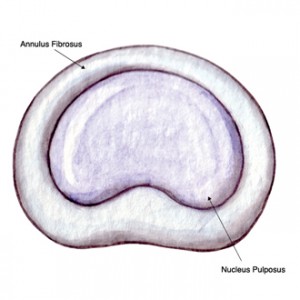

Intervertebral Discs: Between each vertebral body is a cushion, the intervertebral disc. Discs absorb stresses the body incurs during movement and prevents vertebrae from grinding against one another. The intervertebral discs are the largest structures in the body without a vascular supply. By means of osmosis, each disc absorbs needed nutrients. Each disc is made up of two parts: the annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus.

Spinal Cord and Nerve Roots: The spinal cord is a slender cylindrical structure about the diameter of a little finger. Contained and protected within the spinal canal, the spinal cord begins immediately below the brain stem and extends to approximately the first lumbar vertebra (L1). Thereafter, the cord blends with the conus medullaris, which becomes the cauda equina, a group of nerves resembling a horse’s tail. Nerve roots exit the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramen.

The brain and the spinal cord make up the Central Nervous System (CNS). The nerve roots that branch out through the foramen into the body form the Peripheral Nervous System (PNS).

Tendons and Muscles: Tendons are similar to ligaments, except these tension-withstanding fibrous tissues attach muscle to bone. Ligaments attach bone to bone. Tendons consist of densely packed collagen fibers.

Muscles, either individually or in groups, are supported by fascia. Fascia is strong sheath-like connective tissue. The tendon that attaches muscle to bone is part of the fascia. The muscular system of the spine is complex, with several different muscle groups playing important roles. Muscles in the vertebral column provide spinal support and stability and serve to flex, rotate, or extend the spine.

OrthoManhattan boasts some of the top New York spine specialists in both experience and bedside manner. Dr. Jonathan Stieber is one of the most accomplished spine surgeons in the field, and he would love nothing more than to get you back to pain-free living.

The New York spine specialists at OrthoManhattan treat a variety of spinal anatomy conditions and injuries. If you’re living with back or neck pain, make an appointment with the New York spine specialists at OrthoManhattan! Your spine is such a major component of the human body; it’s vital that you make sure that it’s as healthy and protected as possible.